It's been almost four years since I posted here. Sorry. There are reasons: busy, sick, grieving, joyful, distracted.

I submitted this to the New York Times' Modern Love feature thinking it might be an interesting take on Mother's Day, but they didn't take it so I decided to add some photos and post it here. Happy Mother's Day.

Beep. Beep-beep. Stop, kneel, dig, hold, examine.

I’m metal detecting an old farm field on the outskirts of Nashville and thinking about my mom.

In the palm of my glove lies the target: a rusted bottle cap. Whee. I hold it up to the sky and yell, “Happy Mother’s Day!” I sometimes speak in this concerning manner because I’m finally allowed to talk to her.

I drop the pull tab into my fanny pack and move on, swinging my Fisher F75, which is the finest and most magical of machines.

|

| i don't normally hug my detector. |

|

| bottle caps were once useful, but now are disappointing. still, they deserve to be posed near knockout roses. |

For the last decades of my mother’s life, I spent my birthday and hers, but especially Mother’s Day, wondering what she was doing and if she might be thinking with some sort of fondness of her only child. Once she achieved the cessation of her successful, cultured, New York City speech teacher life by dying nearly alone in her Sutton Place apartment, I stopped wondering what she was doing on those admittedly meaningless marker days. Instead, I was suddenly free to learn as much as I could about the woman who birthed me, raised me to adulthood, then cut me out of her life like a tumor.

Beep beep. Beep. Stop, kneel, dig, slice through annoying root, hold, examine. 1941 Mercury. Nice.

|

| so pretty. |

She was born in Mississippi, the white-blond eldest of three daughters, and grew up picking cotton and helping her daddy gather pecans.

|

| this is the kind of truck that would have thundered down the dirt road in front of the farmhouse where she grew up. |

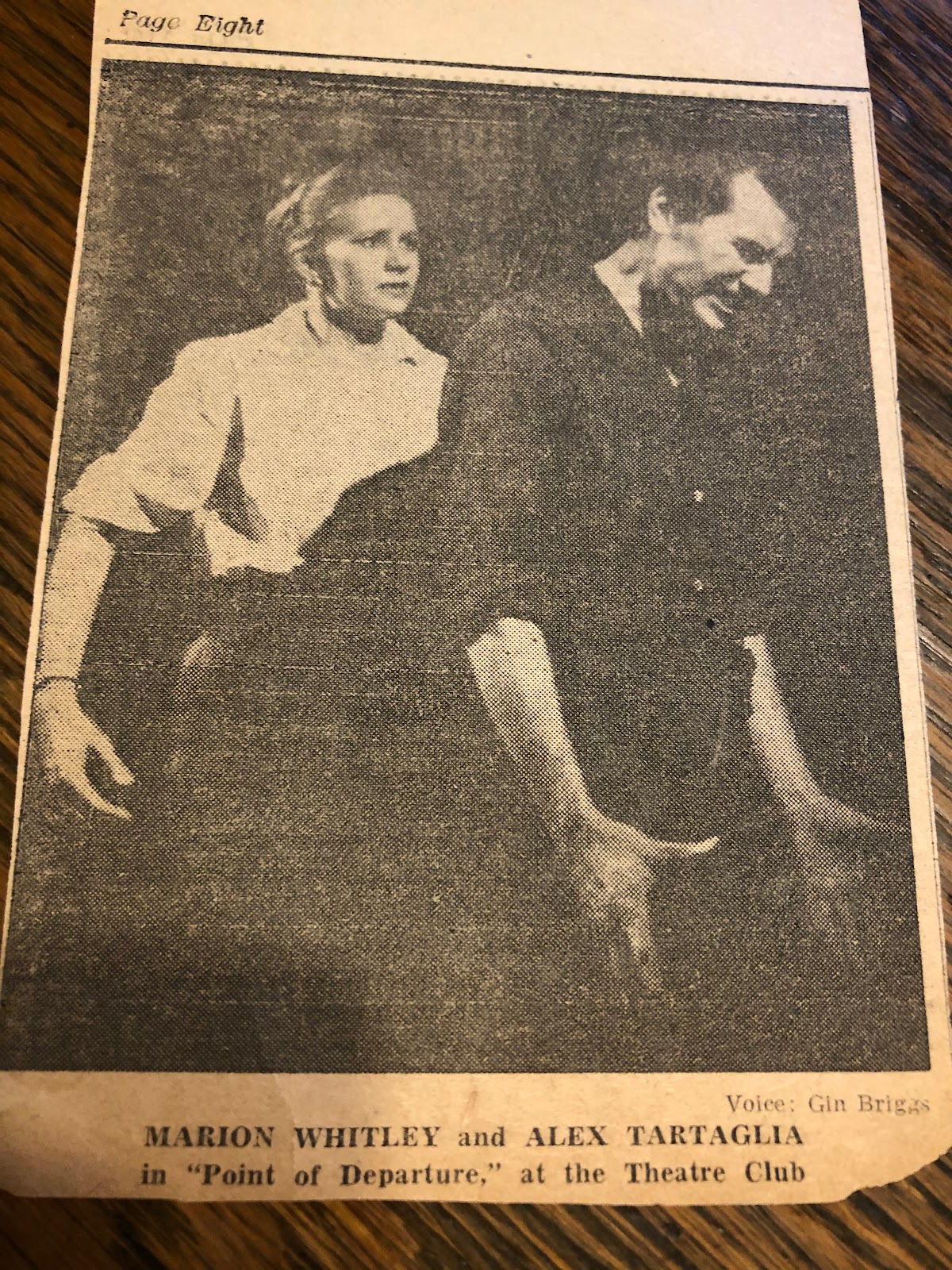

She told me once that while sitting in the outhouse, clutching a magazine intended for other purposes, she learned that there was a place called New York City, and that it had “delicatessens.” The city became her tractor beam. She met my father—a full-blooded Armenian from Appalachia—while doing summer stock and they moved to the city to become actors. A few years later, and despite her best efforts, I appeared in her uterus. This caused all sorts of dismay, the end of my parents’ marriage (and my mother’s dreams of theater) as well as the start of a mother/daughter relationship with a sell-by date.

|

| i found this in her belongings. |

|

| this is a music box that doesn't make one sound. |

But if she was going to do this mother thing, she was going to do it right: a progressive preschool, dance and piano lessons, horse camp, French camp, world travel, and a delightful disregard for rules. I wanted to stay home from school to write a story about an avocado? Of course, I could. And I did, in 15 minutes, then spent the rest of the day crouched in front of the portable Zenith eating Snow Caps. On the bookcase above the TV stood bronze sculptures of us—a hollow-eyed bust for her, and me as the little Degas ballerina, albeit with quite a tummy. This was a love for the ages; the two of us in our one-bedroom, roachy micro-apartment, living our best enmeshment, while padding about on Oriental rugs. “Ours is a charmed life, my daughter,” she told me over and over. I believed her and loved her with all I had.

|

| she wanted me to be a dancer. luckily, i was one, for a long time. but it was not enough. |

There were clues of what was to come. The letters I ripped open at camp often closed with some version of “I thought I would miss you, but I don’t. Mom.” There was the occasional and entirely unwarranted crack across the face. There were the many trips to various neighborhood liquor stores, which I loved because they smelled like paper. But I was just too close to it—and too alone—to know what I was dealing with: an actress playing a part. Luckily, happily, my dad was a natural and enthusiastic parent; his resilience and optimism shaped me as I grew.

|

| an item i want. an item i don't want. an item i both want and don't want. |

Beep. Beep beep.

Beep.

I dig and dig and dig. Ooh, look: a silver dime from 1848. A few steps later, another signal: part of a Dr. Pepper can.

|

| i do have a part of a dr. pepper can in the trunk of my camry, but i'm too lazy to photograph it so here is a 4. |

At 22, I was back from college living in a Soho loft with a brooding boyfriend and attempting to “be a dancer.” It was pretty much what my mother had raised me for: a life in the arts, one untethered to convention, filled with inquiry and adventure. Though we saw each other regularly, she seemed increasingly tense and distant; I’m sure I was too wrapped up in my own life to ask why. On a hot September day, I sat on her sofa and told her I was going to have a baby. For a long minute, she stared out the window at the traffic hurtling up First Avenue, then turned toward me, unrecognizable.

|

| this, too, is unrecognizable. no one knows what it is. even experts. |

“Get it taken care of.” Her words: rusted machinery, jolted to life. I knew exactly what she meant and I swear, she showed her teeth.

“No, I don’t want to…do that. It’s OK! We’re gonna get married!”

“You’ll be barefoot and pregnant like the rest of them.”

“What? No! I can do this Mom. I want to do it.”

“Then there can be nothing more between us.”

And with those words, she was free of me.

|

| and it was like a stake to the heart. this is not an actual heart stake. but it certainly could be used that way. |

My boyfriend and I had a grim little wedding in a Greenwich Village church, then moved to Cape Cod where I gave birth to my daughter in an 1830s house on a soft spring evening. Not long after, a box arrived with no return address, filled with the detritus of my childhood: dolls, doll furniture, crumbling crayon drawings, adoring love notes with backward “e”s, letters I’d sent her from college. I put it away.

|

| this is my daughter. she just sent me a beautiful mother's day gift. i'm so glad i stuck to my guns. |

|

| and this is another beautiful find. it had been hit by a lawn mower, but i had it repaired. |

We moved to Michigan where I founded a dance company and our son was born. This makes it sound as if I moved on with my life easily, but those years—and many to come—though filled with art, friends, divorce, remarriage, and the joyous chaos of tending to small, sticky, hilarious humans, were weighted with the loss of my mother. I sometimes wondered if I’d done a truly terrible thing–murder, perhaps? Klan membership?–and somehow forgotten about it. I never gave up, sending her letter after letter, some pathetically chatty—as if nothing had happened—others pleading, outraged, demanding to know why, how this could have happened. Silence from my phantom limb.

It was challenging explaining her absence in my life to others. My children, whom she never met and whose names I assume she never learned, grew up knowing that mothers, even once-beloved ones, can and do abandon their young. They processed this in their own ways. When my son was five, he burst into tears one night, thinking of his grandmother alone in New York. “We have to call her, mom! She needs us! Can we call her? Now?”

|

| there was no one to call for help. she didn't want our help. she wanted to be free. to not be a mother. |

If a new friend asked me about my mother, I had a few sad, stock answers:

“We’re not very close.”

“Yeah, she died a long time ago.”

“She lives in New York. I mean, I guess you could call it living…” (This one shut the topic down and became my go-to.)

|

| this sterling silver child's knife handle is the only item i ever dug in new york city. |

But in fact, with me out of the picture, my mom exploded into living. She traveled every corner of the world, spent two years in the Peace Corps, wrote her memoirs, and developed deep, enduring friendships. Meanwhile, our “estrangement” (a polite word for what felt to me like dismemberment) had blighted every leaf of our family tree. My good, sweet, Southern relatives never stopped loving me, but they also fell in line with my mother’s directives. If she was within earshot, I was rarely mentioned. If she planned to visit for Easter, I was gently advised to stay away that year. When names were drawn for a Secret Santa gift exchange, my aunts made sure the tiny slips of paper my mother and I received bore safer names. “It was like a bomb went off in our family,” my cousin told me recently.

In my darkest midnight moments, I cycled through questions: Had she ever loved me at all? Was my upbringing an elaborate performance?

Was that kind of ruse even possible?

Did she ever dream about me?

Soon after moving to Nashville with my second husband, I bought a metal detector from a man at a gas station. Bizarrely, this uncool hobby stilled the roiling questions and gave me hours and hours of peace as I roamed forests and fields, digging into the earth.

|

| i am adept at finding round things. |

One morning during a pandemic summer, my aunt called me.

“Hey, little chick,” she said. “I can’t reach your mother. She hasn’t answered her phone in five days.” I’d always wondered how this would go. My aunt eventually tracked my mother to a hospital where she was recovering from surgery; she wouldn’t say what had happened. Though groggy from drugs, she was emphatic: No one was to come help her. Her plan was to “go home and die in three weeks.”

|

| she was not religious. at all. but somehow this feels appropriate. |

And that’s pretty much what she did. At my request, my aunt bravely asked my mother if I could send her a card. Her response: “What would be the point?” I stared at the card, already written, addressed and stamped, then put it in the recycling.

A week later, my mother’s attorney called to tell me she was gone and I wailed the singular, strangled wail of the excised daughter as my husband gathered me tight. Flustered, the attorney tried to soothe me by telling me my mother left me her belongings and some money, but this confusing information did nothing to stop the torrents of necessary sound. See, I just never could quite bring myself to hate her.

The attorney gave me the phone number of my mother’s closest friends, two women I’d never heard of. I stood in my driveway, called them, and learned that through decades of friendship, she had never mentioned she had a daughter. Even though the information stung, I discovered that knowing it felt oddly empowering. What else could I learn, now that she was gone?

Beep. Beep beep. It’s a faint signal, this one. I dig deep into Tennessee dirt, then set my spade aside and use my fingers, feeling for something dropped and forgotten, but I never find it. Sometimes that happens.

Back home, I peel off my jeans and stand barefoot on the threadbare Turkish carpet I learned to walk on. Around me are boxes of her life: manuscripts, photographs of strangers, her travel journals—and all the letters I ever sent her, unopened.

I’ve been going through everything, trying to understand. There’s something in here, somewhere.